During the production period in the summer months of 2017, Janette Kerr kept a blog which is reproduced in part below about the making of the work:

Documents

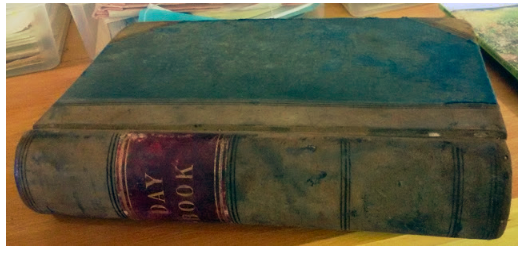

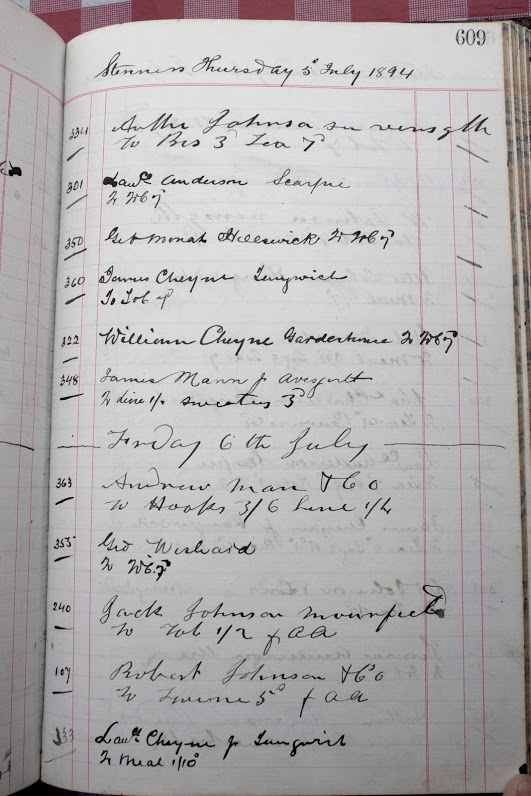

In between filming and recording we collected information about the lodges and shops that were used by the men during the fishing season. The beautiful Day Book, which is part of the collection at Tangwick Haa Museum, is a testament to the coming and goings from one of the shop at Stenness during the fishing season.

In the Shetland Archives we read handwritten 19thC documents about Stenness, and listen to oral recordings of fishermen James Cheyne and Christie Irvine recalling days at Stenness and the fishing. We attempted to transcribe some of these records with the names of fishermen working at Stenness, detailing the daily catch of ling and cod by each sixareen crew. This information would be noted by the Laird’s factor to set against the men’s other debts – rent and purchases in the Laird’s shop – as noted in the Stenness Day Book – and which would often exceed the money earned during the fishing season, leaving the men in debt. The day book documents the names of fishermen occupying the lodges, what they were buying – the price of rope, tea, hooks, ‘counterpanes’ and ‘sweeties’ and even cigars.

Gutting

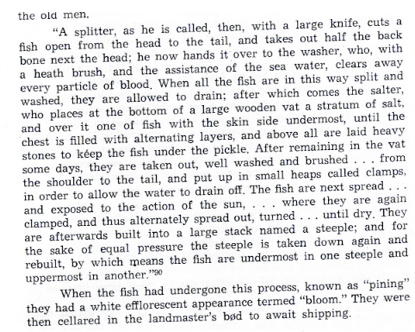

After a dash into Lerwick to LHD Ltd we collected two large ling and a Cod recently brought in for us by the Guardian Angell fishing boat. On the west side we met up with Steve Anderson and family to film him splitting and gutting of the ling on the beach. There was much discussion of the ways that ling were split and each new description we read seemed to differ from the last…

Other descriptions have the fish gutted on board the boat as the men returned from the far haaf, while others have the whole process taking place on the beach. It probably depended on circumstances and how many fish had been caught, the weather. Ling and Cod were all cleaned and salted and stacked in barrels, and laid out on the stone beaches to dry, turned and then stacked by the beach boys and old men, who also had to keep the seabirds at bay.

Recording voices and music

Shetland’s own musician Catriona MacDonald came to Stenness and we recorded her playing the Shingly Beach tune composed by the famous Tammy Anderson. Set against the sounds of the sea and birds it was pretty special.

People very generously came to the beach and gave us their time and voices and we made some wonderful oral recordings, of extracts from the Day Book (kept at Tangwick Haa Museum) noting daily purchases from the Bød when once it was a shop, from the Fishermen Agreements Book and from records of the Ling fishing (kept in Shetland Museum & Archives). The names of the fishermen who once inhabited the lodges and worked on this beach floated into the air, merging with the sounds of sea birds and the sea pushing and pulling on the shore.

Kite flying

There were kite flying trials. The problems of having a GoPro on the end of a kite up in the air and being taken wherever the wind decides to pull is that you never know what you are filming. So the results were hit and miss, but a slightly random approach made for more abstract images. In the end we didn’t use any of this footage.

Bell ringing

Having found references to a bell marking the beginning and end of work sessions at the fishing station we experimented with recording different bell sounds. It’s remarkable how many different ways there are to ring a bell and how much the sound varies from different locations around the beach and the ways of recording.

‘ The curing and drying of fish taken at the Stenness Haaf is … conducted with great regularity, a bell ringing for the cessation and resumption of labour’.

Photographing and filming the ruined lodges scattered around Stenness beach.

Slowly as we filmed and walked on the beach it began to emerge as a place of work. The more the remains of the lodges became visible. Most have disappeared, swept away over the last 100+ years by the action of wind and sea and stones plundered over the years since last occupied in the 19thC to build walls and houses elsewhere. They would have been agreeable to 18th C William Gilpin’s definition of the picturesque as ‘that kind of beauty which is agreeable in a picture’ and for whom a bit of a ruined abbey or castle with rugged edges would add ‘consequence’. Looking out to sea we imagined the sixareens pulling away from the shore, the land gradually disappearing as they rowed out to the far haaf and the noise of the men working and living on the beach.

From 19thC newspaper reports in the Shetland Times it is clear that fish were not always plentiful during the season. In addition to light loads, the fishermen were plagued by ‘swarms of hoes’ (which we think are dog fish) which prevented them catching the white fish.

What the diet of the men consisted of and whether they were well nourished or not, living in such close proximity in pretty rudimentary conditions meant that illnesses spread pretty fast. It seems that, as usual, the unsettled Shetland weather – thick fog and gales – also put paid to successful fishing trips.

At the end of the season in August 1877 Laurence Anderson is noted as having taken the highest yield at 315cwt. But chief topic of conversation was the ordinance survey that was going on that year, with complaints of wheat fields being trampled in the process of mapping and threats of giving the boys a dipping in the sea if they were seen in the corn again.

Tommy Isbister

A visit to Mary and Tommy Isbister on Tronda we learned more about building sixareen boat, splitting ling, and haaf fishing

Tom Williamson

Local Tom Williamson took us out from Stenness beach in his creel boat which meant that we could gain a sense of the experience of leaving from Stenness Beach as the sixareens had once done; of what the Haaf fishermen would have seen as they rowed out to the fishing grounds, the land and Böd behind them slowly receding, before them the open sea and far horizon.

During the fishing season from around Beltane Day in May to Lammas Day in August their days and nights were spent travelling in open boats between shore and far haaf setting lines and hauling the fish until there was a full catch in the boat and they could turn and head back to shore. Men sometimes rowed for nine hours, although weather permitting and with a good wind behind them, with the sheet raised this would have taken them to the far haaf a lot faster. A hard life, and one in which they didn’t have much say but to go to the fishing, given pretty much all they had was owned by the Laird.

The day we went out there was a brisk wind and choppy seas, mist hanging over us, but the fishermen would have experienced far heavier seas running on occasions. Being so low in the water the land disappears the further out we travelled. Even so, rowing Foula down with its high cliffs, would have been some feat. Any bit of land would have acted as a marker – a meid from which to orientate their position. As Tommy Isbister remarked ‘when you were sitting down in a boat ..when the land was sinking you knew where you were’. These men would have known their sea, could read how the water was running, and most of the time knew how the weather would be. Despite this there were times when there was heavy storms and loss of life.

Returning from the haaf fishing the first sight of the beach would have probably been the chimneys of the Böd rising above the hills, or smoke rising from the lodges.

On the beach the ling and cod would be washed, salted, and laid out on the stone beach by the beach boys and old men, while, after a few hours rest, the men returned to the sea. Bleached white by sun and air, the white fish, so prized on the continent, would be stacked and then weighed by the factor and a record made of each boats catch..

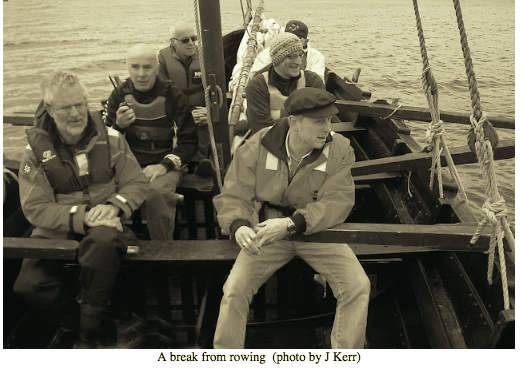

Sixareens and The Vaila Mae

Mustering at the museum the excellent Brian Wishart assembled our fine rowing crew from various parts of Shetland – all well qualified and skippers in their own right. The boat made ready we spent a morning filming the beautiful Vaila Mae. The sounds of the oars rising and dipping, with square sail up to catch the wind she just flies along through the water is wonderful to experience. You also begin to understand how such boats were able to travel so far out to the far Haaf, although the fishermen must have had a cold, wet and cramped time living in the boat, often sleeping under the sheet for several nights until they had a full catch and could return to the fishing station.

The sixareen was best suited for the prosecution of the white fishing. With a keel about two thirds of the overall length, flaring outwards to the gunnels, like the Viking ships, inside it was divided into compartments by gratings under the benches where the men sat to row. With working sections to hold the fish, the bottom of the boat would be filled with ballast of beach boulders until ready to be replaced by the caught fish. Sitting on top of a run of fish secured down by netting made the boat more stable and less likely to take on water. In the owse room the flooring was higher so the shovel might have a smooth sweep from one side to the other when bailing. The mid room was for shooting and hauling lines, which could be 6 miles in length.

When the first fish showed ‘light in the lum’, then ‘light below that’, followed by ‘white below white’, hauling a line laden with struggling fish weighing 30 – 40 lbs per cod and ling, plus Halibut weighing 2 cwt and gigantic skate, all hauled from depths of 30 to 90 fathoms must have been a supreme test of strength, even with the boat being pulled by a couple of oars in the direction of the line. The foreroom held ballast, fire kettle and pot, plus peat fuel; the head room and bow-space were culinary areas holding a sea chest for knives and utensils and food, along with water breakers, sail, six miles of line, 5000 baited hooks, buoys, sinkers, spare rope, boat hooks, oars, oilskins etc etc.. All of which, with a mast lying somewhere in the mix, didn’t leave much room for manoeuvre in a boat containing six large fishermen rowing, a skipper at the stern trying his best to avoid the breaking sea that could flood in, and the bailer trying to keep the sea at bay, all hauling and gutting fish, and in between, eating and sleeping.

Shetland fishermen were unsurpassed in their handling of these open boats, rowing the 30-40 miles to the fishing grounds. But very few fishermen would have owned their own boats, most being owned by the landowners who hired them out for the fishing season, which of course meant if the boat was lost it had to be paid for, often by a grieving widow and children, who, not being able to pay, would be evicted from the croft. In 1774 a six-oared boat complete with mast, square sail and oars cost about £6 and measured 18ft on the keel, 24-25ft overall.

‘…..out at the Haaf, before the compass came into general use – with the fog and tidal currents prevailing….. here the men of old had means of finding their way to land…. an underswell – the moder dye – the surge or physical protest the Ocean makes when her cosmic motion is restricted by the proximity of land. Unnoticeable in deep water, the wave-like motion or swell becomes clearly discernible to trained eyes on soundings, and can be best observed in foggy weather. … No matter how fierce the gale, how wind-driven and uncertain the billow, the methodical undulations of the ‘moder dye’ could be seen across the hills of a wind-torn sea, always setting four-square towards the land’. Extracts taken from ‘The Sail Fishermen of Shetland’, A Halcrow, pub. The Shetland Times, 1994, 1st published T & J Manson, Lerwick, 1950.Other information taken from ‘Shetland Fishing Saga’, C A Goodlad, pub. The Shetland Times Ltd. 1971, and ‘Inshore Craft of Britain: In the Days of Sail and Oar’ vol 1, Edgar J March, pub.david & Charles, Newton Abbot, 1970.Plus information gleaned in conversation with Tommy Isbister, Trondra, Shetland: Shetland Heritage Association

Acknowledgments

In the course of researching Stenness and the haaf fishing we have consulted many sources. We would like to acknowledge and thank the following people for their help and support:

Rob Gawthrop – sound recording/technical support

Shetland Museum: John Hunter, Ian Tait, Trevor Jamieson, Yvonne Reynolds

Shetland Archives: Brian Smith, Angus Johnson, Blair Bruce

Tangwick Haa Museum: Ruby Brown and Nanette

The Vaila May crew: Brian Wishart, Jim Tait, Gilbert (Gibbie) Fraser, Andrew Cooper, Ewen Balfour, Robert Wishart, Trevor Jamieson

Gary and Andrew from LHD and Guardian Angell skipper for organising and supplying Ling

Steve Anderson for gutting ling, and Lynn McCormack for arranging this

Catriona Macdonald for superlative fiddle playing of ‘Shingly Beach’, written by Tom Anderson

Tom Williamson for creel boat journeys at Stenness

Readers of 19thC texts: Ewan Balfour, John N Hunter, Nancy Hunter, Ruth Fisher, Wilma Stewart, Valerie Watt, Jim Tait, Gilbert Fraser, Margaret Anderson, Peter Sinclair

Tommy Isbister for talking about the fishing

Jonathan Rich (Shetland Arts) – sound installation

Finally Alistair Goodlad, who’s authoritative book Shetland Fishing Saga set us on course.